In this series I’ve been explaining 12-tone scales in just intonation—or more precisely, ‘5-limit’ just intonation, where all the frequency ratios are integer powers of the primes 2, 3 and 5. There are various choices involved in building such a scale. A lot of famous mathematicians have tried their hand at it. Kepler, Descartes, Mersenne, Newton, Mercator, and Euler are among them. They didn’t agree on the best scale: they came up with different scales.

Newton did his work on this in college when he was 22. This was 1665, the year he later fled Trinity College to avoid the Great Plague, went to the countryside, invented calculus, began thinking about gravity, and discovered that a prism can recombine colors of light to make white light.

Given this, I can’t resist classifying all possible scales of this sort. Today we’ll see that by a certain precise definition, there are 174,240 such scales! It will take a bit of combinatorics to work this out. Among this large collection of scales we will also find smaller sets of scales with nice properties. But I still don’t know why those mathematicians chose the scales they did.

In studying this, and indeed in all my work on just intonation, I was greatly helped by this wonderful paper:

• Daniel Muzzulini, Isaac Newton’s microtonal approach to just intonation, Empirical Musicology Review 15 (2021), 223–248.

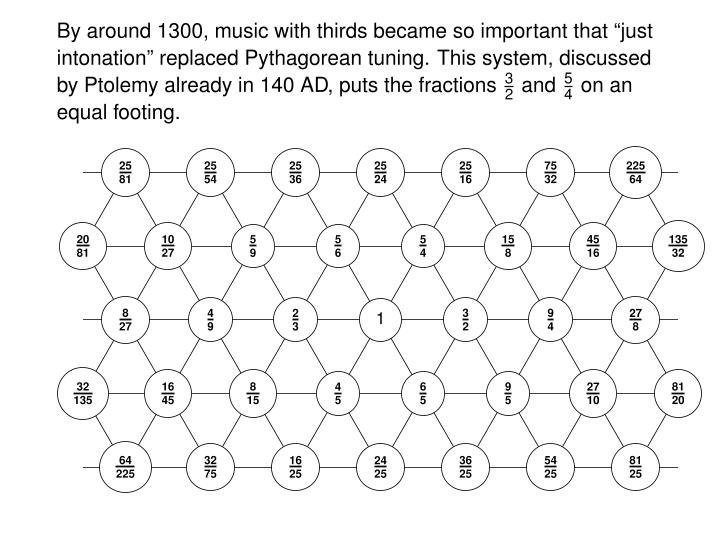

It’s full of interesting diagrams:

Anyway, let’s get going!

In Part 2 of this series, I examined the choices involved in building a just intonation scale. I described a general recipe for building such scales. These leads to 2 × 4 × 2 = 16 different scales, based on how you make the choices here:

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 10/9 or 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

| tritone | 25/18 or 45/32 or 64/45 or 36/25 | |

| perfect 5th | 3/2 | |

| minor 6th | 8/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/3 | |

| minor 7th | 16/9 or 9/5 | |

| major 7th | 15/8 | |

| octave | 2 |

Newton’s scale is one of these 16. Marin Mersenne had created the same scale in 1636, but Newton probably didn’t know this. In fact I studied this scale in Part 4, where I claimed that it’s the most popular just intonation scale of all! It’s hard to be sure of that—but I certainly think it’s the nicest one.

Here it is:

The intervals between the notes come in 3 different sizes, which we will discuss soon. In Part 4, I explained some reasons this scale is nice. For example, the intervals here are nearly palindromic! The first interval is the same as the last, and so on—except right near the middle of the scale, the ‘tritone’, where this symmetry is impossible because it would force to be a rational number.

In Part 4, I also considered another less popular scale among the 16 generated by my recipe:

In this one the intervals come in 4 different sizes! Let’s make up abbreviations for them. In order of increasing size, they are:

• c: the lesser chromatic semitone, with frequency ratio 25/24 = 1.041666…

• C: the greater chromatic semitone, with frequency ratio 135/128 = 1.0546875.

• d: the diatonic semitone, with a frequency ratio of 16/15 = 1.0666…

• D: the large diatonic semitone, with frequency ratio 27/25 = 1.08.

With this notation, Newton’s scale is

I’ll say this scale has type (2,3,7,0) since it has 2 c’s, 3 C’s, 7 d’s and 0 D’s. The less popular scale I mentioned is

This scale has type (3,2,6,1). Arguably this scale is worse, because the large diatonic semitone is quite large compared to all the rest.

Muzzulini also describes some other just intonation scales. Here’s one that Nicolas Mercator created around 1660—not the Mercator with the map, the one who discovered the power series for the logarithm:

This is striking because it has two large diatonic semitones: it’s of type (4,1,5,2).

Here’s one that the music theorist William Holder wrote down in 1694:

This has three diatonic semitones—the most possible! It’s of type (5,0,4,3).

Leonhard Euler came up with this scale in 1739:

This has type (3,2,6,1).

It would be interesting to find out, if possible, why various authors chose the scales they did. Did they scan the universe of possibilities and try to pick a scale that was optimal in some way—or did they did they just make one up? Answering this would require some historical investigation.

All these ruminations led me to some questions about enumerating and classifying scales, which I included as puzzles in Part 4. Now let me finally answer them!

Puzzle 1. As we’ve seen, the most popular 12-tone just intonation scale is of type (2,3,7,0). That is, it has 2 lesser chromatic semitones, 3 greater chromatic semitones, 7 diatonic semitones, and no large diatonic semitones. By permuting these semitones we can get many other scales. How many different scales can we get this way?

Answer. We have a 12-element set and we’re asking: in how many ways can we partition it into a 2-element set, a 3-element set and a 7-element set? This is the kind of question that multinomial coefficients were designed to answer. The answer is

█

Puzzle 2. Our second, less popular 12-tone just intonation scale is of type (3,2,6,1): it has 3 lesser chromatic semitones, 2 greater chromatic semitones, 6 diatonic semitones and 1 large diatonic semitone. How many other scales can we get by permuting these semitones?

Answer. By the same reasoning, we have

such scales. █

These puzzles were warmups for a bigger question:

Puzzle 3. How many 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a lesser chromatic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a diatonic semitone, or a large diatonic semitone?

Answer. The only types of scales allowed are quadruples of nonnegative integers where

or equivalently,

The four numbers

span the 3-dimensional rational vector space with basis so they must obey one linear relation with integer coefficients (and others following from this one). This relation is

This says cD = Cd: the lesser chromatic semitone followed by the large diatonic semitone takes you up to a frequency 9/8 higher, just like the greater chromatic semitone followed by the diatonic semitone.

This means that if a type is allowed, so is

if

Furthermore, it means this move (and its inverse) can take you from any allowed type to all other allowed types.

So, let’s start with the type where the number of large diatonic semitones, is as small as possible. This is our friend

(2,3,7,0)

We can get all other allowed types by repeatedly adding 1 to the first and last component of this vector and subtracting 1 from the other components. Thus, these are all the allowed types:

(2,3,7,0)

(3,2,6,1)

(4,1,5,2)

(5,0,4,3)

We can now use the methods of Puzzles 1 and 2 to count the scales of each type. We get:

= 7,920 scales of type (2,3,7,0).

= 55,440 scales of type (3,2,6,1).

= 83,160 scales of type (4,1,5,2).

= 27,720 scales of type (5,0,4,3).

So, we get a total of

7,920 + 55,440 + 83,160 + 27,720 = 174,240 scales. █

This is a ridiculously large number of scales! But of course, not all are equally good. Let’s impose some extra constraints.

The whole point of just intonation was to make the third equal to 5/4, and we also want to keep the fourth at 4/3 and the fifth at 3/2, as we had in Pythagorean tuning. When it comes to the second, either 10/9 or 9/8 are considered acceptable in just intonation. I like 9/8 a bit better, so let’s do this:

Puzzle 4. How many 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a lesser chromatic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a diatonic semitone, a large diatonic semitone, and:

• the second is 9/8

• the third is 5/4

• the fourth is 4/3

• the fifth is 3/2?

Answer. With these constraints there are 1,600 allowed scales. The idea is this:

• There are 4 ways to go from 1 up to 9/8 in two semitones, since only Cd, dC, cD and Dc multiply to 9/8.

• There are 2 ways to go from 9/8 up to 5/4 in two semitones, since only cd and dc multiply to 10/9.

• There is 1 way to go from 5/4 up to 4/3, since d is 16/15.

• There are 4 ways to go from 4/3 up to 3/2, since only Cd, dC, cD and Dc multiply to 9/8.

• There are 500 ways to go from 3/2 to 2 in five steps. Here we need to count ordered quintuples of c, C, d and D that multiply to 4/3. I did this with a computer.

So, we get 4 × 2 × 1 × 4 × 500 = 1,600 scales of this sort. █

All these scales have the second being the greater major second, 9/8. But you might prefer the lesser major second, 10/9. So let’s think about that:

Puzzle 5. What about the same question as before, but where we constrain the second to be 10/9 instead of 9/8?

Answer. Again there are 1600 scales. In Puzzle 4 our scales went up from 1 to 9/8 by choosing two semitones that multiply to 9/8, and then from 9/8 to 5/4 by choosing two that multiply to 10/9. Now the only difference is that we’re going things in the other order: we’re going up from 1 to 10/9 by choosing two semitones that multiply to 10/9, and then from 10/9 to 5/4 by choosing two that multiply to 9/8. So the overall count is the same as before. █

Since they differ only by switching some semitones, the 1,600 scales with a greater major second have the same distribution of types as the 1,600 with a lesser major second. Using a computer, I calculated that in each case there are

• 160 of type (2,3,7,0)

• 560 of type (3,2,6,1)

• 640 of type (4,1,5,2)

• 240 of type (5,0,4,3).

How can we pick out a smaller number of ‘better’ scales? We’ve imposed a lot of constraints on the tones from the first to the fifth, but none on the tones above that. To impose constraints on the higher tones, we can demand that our scale be palindromic, except that we can’t require that the interval from the fourth to the tritone equals the interval from the tritone to the fifth, because is irrational. So, I’ll call scales with the following properties nearly palindromic:

• the interval from 1 to ♭2 equals that from 7 to 8

• the interval from ♭2 to 2 equals that from ♭7 to 7

• the interval from 2 to ♭3 equals that from 6 to ♭7

• the interval from ♭3 to 3 equals that from ♭6 to 6

• the interval from 3 to 4 equals that from 5 to ♭6.

Puzzle 6. How many nearly palindromic 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a lesser chromatic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a diatonic semitone, a large diatonic semitone, and:

• the second is 9/8

• the third is 5/4

• the fourth is 4/3?

Answer. There are 32 scales with these properties. First note that the above properties force other facts:

• the fifth is 3/4 × 2 = 3/2

• the minor sixth is 4/5 × 2 = 8/5

• the minor seventh is 8/9 × 2 = 16/9.

Thus, we have the following choices:

• There are 4 ways to go from 1 up to 9/8 in two semitones, since only Cd, dC, cD and Dc multiply to 9/8.

• There are 2 ways to go from 9/8 up to 5/4 in two semitones, since only cd and dc multiply to 10/9.

• There is 1 way to go from 5/4 up to 4/3, since d is 16/15.

• There are 4 ways to go from 4/3 up to 3/2, since only Cd, dC, cD and Dc multiply to 9/8.

and from then on, our choices are forced by the nearly palindromic nature of the scale.

There are thus a total of

4 × 2 × 1 × 4 = 32

choices. █

These 32 scales come in two kinds:

• the 16 scales discussed in Part 4, where the minor second is the diatonic semitone, d = 16/15

• 16 others, where the minor second is the greater chromatic semitone, C = 135/128.

Newton’s scale is of the first kind.

All 32 of these scales use the greater major second. A similar story holds with the lesser major second.

Puzzle 7. How many nearly palindromic 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a lesser chromatic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a diatonic semitone, a large diatonic semitone, and:

• the second is 10/9

• the third is 5/4

• the fourth is 4/3?

Answer. By the symmetry we used to answer Puzzle 5, this question has the same answer as Puzzle 6: there are again 32 choices. █

These 32 scales again come in two kinds:

• 16 scales where the interval from the second to the minor third is the diatonic semitone, d = 16/15

• 16 others where the interval from the second to the minor third is the greater chromatic semitone, C = 135/128.

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations! I was lured in by how many famous mathematicians had studied this subject, and I wanted to join the fun.

For more on Pythagorean tuning, read this series:

For more on just intonation, read these:

• Part 1: The history of just intonation. Just intonation versus Pythagorean tuning. The syntonic comma.

• Part 2: Just intonation from the Tonnetz. The four possible tritones in just intonation. The small and large just whole tones. Ptolemy’s intense diatonic scale, and its major triads.

• Part 3: Curling up a parallelogram in the Tonnetz to get just intonation. The frequency ratios of the four possible tritones: the syntonic comma, the lesser and greater diesis, and the diaschisma.

• Part 4: Choices involved in just intonation. Two symmetrical 13-tone scales, and two 12-tone scales obtained from these by removing the diminished fifth. The four kinds of half-tone that appear in these scales: the diatonic, large diatonic, lesser chromatic and greater chromatic semitones.

• Part 5: Frequency ratios between the four possible tritones in just intonation, and how they are related to frequency ratios between the four kinds of half-tone. The syntonic comma, lesser and greater diesis, diaschisma, and the relations they obey.

• Part 6: Classifying all 174,240 12-tone scales where the intervals between successive notes are always diatonic, large diatonic, lesser chromatic and greater chromatic semitones. The scales of Isaac Newton, Nicolas Mercator, William Holder and Leonhard Euler.

For more on quarter-comma meantone tuning, read this series:

For more on well-tempered scales, read this series:

For more on equal temperament, read this series:

Posted by John Baez

Posted by John Baez