You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Zbąszyń’ tag.

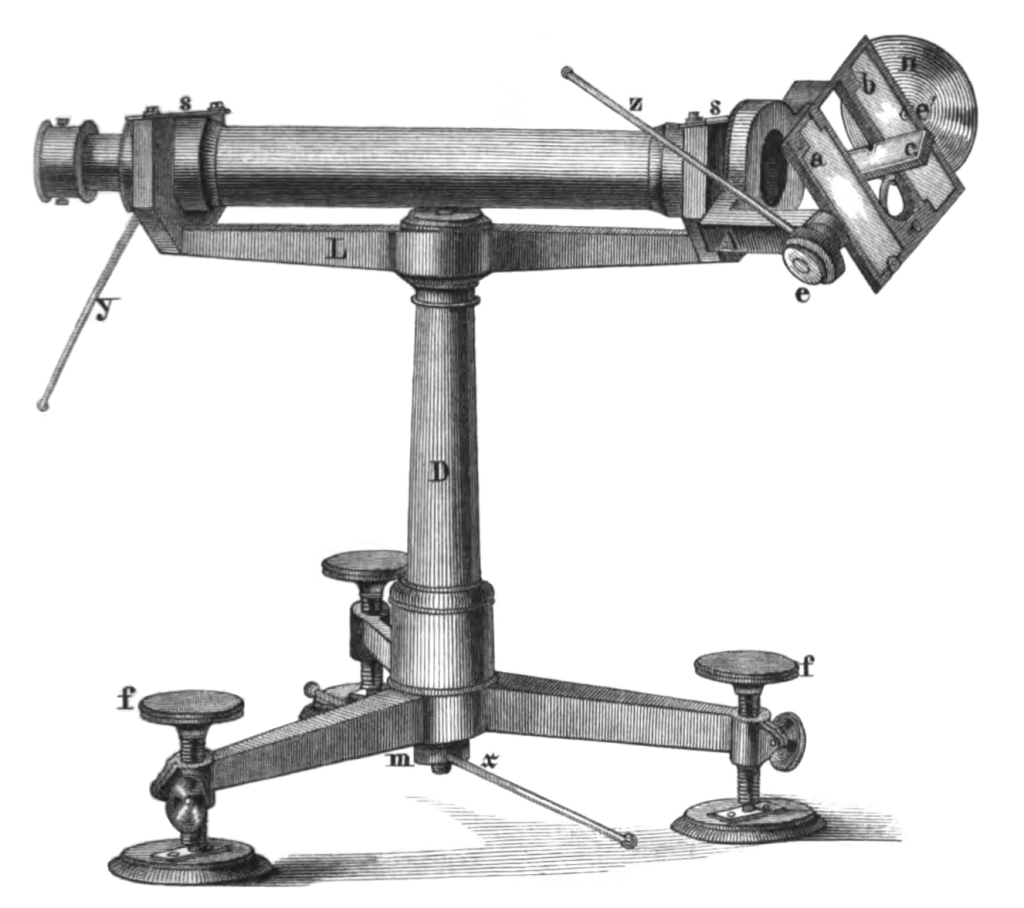

The mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss invented the heliotrope for long-distance surveying in 1821. Just a year later, he proved that least squares regression provided the BLUE estimator for data with uncorrelated Gaussian errors (with mean zero and equal variance). The heliotrope tool and the least squares method allowed Gauss to perform a geodetic survey of the Kingdom of Hanover by triangulation between 1821 and 1825, an unprecedented accomplishment at the time.

Gauss’ approach was scaled up massively by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, who in 1838 published an epic triangulation based survey of East Prussia and parts of Russia in Gradmessung in Ostpreußen und ihre Verbindung mit Preußischen und Russischen Dreiecksketten. His work included understanding for the first time how to calculate the standard error of the mean (which led him to introduce Bessel’s correction), providing an important assessment of how errors in individual measurements during triangulation contributed to overall errors from the least squares procedure. The scale of his survey (~3x Hanover) was arguably also the first use of statistics for big data. Bessel may have been the first ̶m̶a̶c̶h̶i̶n̶e̶ ̶l̶e̶a̶r̶n̶i̶n̶g̶ AI disruptor in history. And he did it not from silicon valley but from Königsberg (now Kaliningrad).

Bessel’s work enabled the completion of the first cross-country rail line linking a Western European capital to an Eastern European capital. The rail line, between Berlin and Warsaw, was completed in 1848 and was a quantum leap after the first national long-distance rail between Leipzig and Dresden in the Kingdom of Saxony was completed in 1839. At ~500km, Berlin-Warsaw was much longer than any previous international crossings. The distance was long enough that Bessel was able to use his triangulation to show that the earth is an oblate spheroid (the method dates to 1825) and in 1841 he established the ellipsoid major and minor axes a = 6377397.155 m, b = 6356078.962822 m. His accuracy was amazing; the WGS84 modern world geodetic system from 1984 is almost the same with a = 6378137.0 m, b = 6356752.30 m. As of 2010 the Bessel ellipsoid was still the geodetic system of choice in Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic.

The Berlin-Warsaw line of 1848 crossed the Prussian-Russian border near the Prosna river, west of the town of Łowicz, which is just under 100km west of Warsaw. Warsaw at the time was part of Congress Poland formed at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, although by the mid 19th century the territory was fully under Russian administration ruled directly by the Tsar. The border moved in 1919 as a result of the Treaty of Versailles after World War I, when a new Polish Republic was established. At that time the border crossing on the Berlin-Warsaw rail line shifted to the town of Zbąszyń (a medieval Polish name for the town, which the Germans had renamed to Bentschen when the town came under Prussian control in 1793).

In the 19th century Zbąszyń was what today we might today call a “multicultural town”. Out of a population of ~1,300 in 1833, there were 336 Jews (~25%), about 35% Germans, and approximately 40% Poles. In other words, there were more Poles than Germans, but Poles were a minority with respect to Jews and Germans. The percent Jewish population in Zbąszyń, which dates back to at least 1437 when it is known that a Jew named Palto sued a nobleman for failure of repaying a loan, peaked in the early 19th century. The reasons for a decline in Jewish population over a century were manifold, but a major factor was antisemitism, including regular blood libels and pogroms in neighboring cities of which a partial list is the “forgotten” Warsaw pogrom in 1805, pogroms in Gdańsk in 1819 and 1821, the Kalisz pogrom of 1878, the Warsaw pogrom of 1881, the Łódź pogrom of 1892, the Częstochowa pogrom in 1902, and the Białystok and Siedlce pogroms in 1906. Many Jews, including in Zbąszyń, fled west, or even abroad. By 1919 when Zbąszyń became part of the Polish Republic (it was deemed Polish in the Versailles treaty on the basis of a majority Polish population), the Jewish population had declined to under 10%, part of a mass migration from Eastern Europe totaling around 3 million Jews.

One couple that emigrated was Zindel Grynszpan and Rivka Grynszpan, who lived in Dmenin near Radomsko just south of Łódź, and moved to the city of Hanover in the Kingdom of Hanover, Prussia in 1911. The Grynszpans started a family in Hanover and eventually had six children, although only three survived into adulthood. The youngest was a boy named Herschel Feibel born in 1921. The Grynszpans were never German citizens; after the Polish Republic was established in 1919 they were recognized as Polish citizens, since they had been born in what was deemed in 1919 to be Polish territory (although in the 19th century Radomsko was part of the Russian empire). Herschel was born in Hanover, but due to the jus sanguinis principle of the German Citizenship Law which came into effect in 1914 (citizenship by descent, not birthplace), he was a Polish, not German, citizen.

On the 28th of October, 1938, the members of the Grynszpan family, along with thousands of other Polish Jews living in Germany, were deported via train to Zbąszyń, the town that happened to be the border town on the Berlin-Warsaw line.

The conditions of this deportation were horrific. Deportation notices technically gave 24 hours to leave but many individuals were deported minutes after receiving a knock on the door, and were not allowed to bring much more than the clothes on their back. How this came about is a sad and sordid story. On March 31, 1938, a Polish law came into effect that revoked the citizenship of Poles who had lived abroad for more than five years. This law was enacted specifically to prevent Jewish Poles from returning to Poland after the Anschluss, i.e. the German annexation of Austria on March 12, 1938. On the 9th of October Polish authorities added a regulation that required passports issued outside of Poland to receive a special consular stamp in order to be valid. In other words, Polish Jews were being stripped of their citizenship. This served as a pretext for German authorities to kick Polish Ostjuden (eastern Jews) out of Germany, and in what has come to be termed “Polenaktion”, they proceeded to dump Polish Jews, many of whom had just been rendered stateless, at Zbąszyń. Below are two first-hand accounts of what the deportation and arrival in Zbąszyń was like:

Your parents were Ost Juden [East European Jews]. Was your family involved in the expulsion to Zbąszyń?

I am so surprised that nobody mentions this, which happened on the 28th of October, 1938, ten days before the pogrom. In our Jewish school the boys were praying in the morning. The girls didn’t have to, but they had to prepare breakfast for the boys to eat after praying. It was the turn of my friend and I to make the tea and we had to be at school at 7:00 instead of 8:00. I was already dressed and ready to leave the house when I heard knocking at our door. When I opened the door, two tall policemen were standing at the door. They asked, “Where are your parents?” I told them they were asleep. “Wake them up, you are going to Poland.” I answered, “What? What do I have to do with Poland? I was born in Germany.” He said, “Take me to the bedroom of your parents.” They both went into their bedroom and put on the light and said, “Get up. You are going to Poland.” My mother thought it was a bad dream. They said, “Don’t ask questions, you are going to Poland.”

My father thought there was a problem with his income tax returns. My mother told me to wake up my 16-year-old brother. My parents asked why they were going to Poland – could they take something with them? The policemen said, “You are going to such a cultural land.” (When Germans talked about Poland they said “dirty Poles”). “No,” he said, “don’t take anything with you.” My father phoned his brother and asked him to take the keys to our apartment. He asked my father, “What have you done?” My father answered, “Nothing.” My aunt came and took the keys but when she got home, the police were in her house, and they really were sent immediately to Poland.

I will never forget my neighbor. She was a widow. She was wearing her nightgown, had hastily put on her overcoat and was carrying a little handbag. When I asked her why she wasn’t dressed, she told me the police didn’t give her time.

We were taken and crammed in to the gymnastics hall of the Jewish school. We saw all the people we knew from the neighborhood who were of Polish origin. My father had very high blood pressure and he couldn’t breathe. He called a doctor who said, “This man has to go hospital, he can’t be transported.” My brother said, “We will never see you again. We will be in Poland and you will be in Germany.” Every half hour a bus came to take the people to the railway station. My mother didn’t want to push, so we took the next bus and as we got in people were pushed in with us. We were all standing and that way we arrived at the Leipzig railway station. On the way, one woman became crazy. They took us to a siding where they take animals, horses and cows. There were soldiers with bayonets standing every ten meters to make sure we didn’t run away. So you see, at 7:00 in the morning I was a student, and at 5:00, I was a criminal. It was terrible (source: Yad Vashem interview with Miriam Ron)

My dear ones!

You have probably already heard of my fate from Cilli. On October 27 of this year, on a Thursday evening at 9 o’clock, two men came from the Crime Police, demanded my passport, and then placed a deportation document before me to sign and ordered me to accompany them immediately. Cilli and Bernd were already in bed. I had just finished my work and was sitting down to eat, but had to get dressed immediately and go with them. I was so upset I could scarcely speak a word. In all my life I will never forget this moment. I was then immediately locked up in the Castle prison like a criminal. It was a bad night for me. On Friday at 4 o’clock in the afternoon we were taken to the main station under strict guard by Police and SS. Everybody was given two loaves of bread and margarine and was then loaded on the freight cars. It was a cruel picture. Weeping women and children, heart-breaking scenes. We were then taken to the border in sealed cars and under the strictest police guard. When we reached the border at 5 o’clock on Saturday afternoon we were put across. A new terrible scene was revealed here. We spent three days on the platform and in the waiting rooms, 8,000 people. Women and children fainted, went mad, people died, faces as yellow as wax. It was like a cemetery full of dead people. I was also among those who fainted. There was nothing to eat except the dry prison bread, without anything to drink. I never slept at all, for two nights on the platform and one in the waiting room, where I collapsed. There was no room even to stand. The air was pestilential. Women and children were half dead. On the fourth day help at last arrived. Doctors, nurses with medicine, butter and bread from the Jewish Committee in Warsaw. Then we were taken to barracks (military stables) where there was straw on the floor on which we could lie down….

H.J. Fliedner, Die Judenverfolgung in Mannheim 1933-1945 (“The Persecution of the Jews in Mannheim 1933-1945”), II, Stuttgart, 1971, pp. 72-73 (source: Yad Vashem).

In total, around 17,000 Polish Jews living in Germany were deported and left stateless on the Polish border; about 8,000 of those arrived in Zbąszyń. Herschel Grynzspan was not with the rest of his family when they arrived in Zbąszyń, as he had left for Paris in 1936. The story of how Herschel arrived in Paris is briefly as follows: his family had intended for him to emigrate to British Mandate Palestine, but he was refused entry by the British for being too young. His parents therefore decided that he ought to emigrate to Paris instead, where they expected he could find refuge with an uncle and aunt (he was 14 in 1935). He eventually left for Paris, albeit his entry to France was illegal because he had no financial support and it was illegal for Jews to take money out of Germany by the mid 1930s.

On the 3rd of November, 1938, just five days after the arrival of his family in Zbąszyń, Herschel received a postcard from his sister Berta detailing their plight. While the Germans had discarded thousands of Jews in Zbaszyn, Poland was unwilling to accept them into the country. The Jews at the border were therefore effectively stateless and unwanted, squeezed into a border town where they were dumped in horse stables, a flour mill, military barracks, or left to sleep outside in fields. Emanuel Ringer, a social worker who went to Zbąszyń to help wrote the following on December 6, 1938 (full letter here):

“Jews were humiliated to the level of lepers, to citizens of the third class, and as a result we are all visited by terrible tragedy. Zbąszyń was a heavy moral blow against the Jewish population of Poland. And it is for this reason that all the threads lead from the Jewish masses to Zbąszyń and to the Jews who suffer there.”

The text in the postcard from Berta to her brother Herschel is reproduced below (source: Federal Archives, Berlin, R 55/20991, letters to and from Herschel Grynszpan):

Dear Hermann [German rendering of Herschel]!

You will surely have heard of our great misfortune. Let me describe what happened. On Thursday evening, rumours were circulating that all Polish Jews were to be expelled from a city. Even so, we found them difficult to believe. On Thursday evening at 9, a policeman came to us and told us that we should go to the police station with our passports. All together, as we were, we went to the police station accompanied by the policeman. We found almost our entire district gathered there. A police car immediately took us to the city hall. Everyone was taken there. No-one told us what was going on. However, we could see what they had in mind.Each one of us was handed an expulsion order. We were told we had to leave Germany before the 29th. We were no longer allowed to return home. I begged them to allow me to go home to at least collect a few things. I then left for home, accompanied by a policeman, and packed the most important items of clothing in a suitcase. That’s all that I was able to save.

We don’t have a single penny on us. […] I’ll tell you more next time

Love and kisses from us all

Berta

Zbąszyń, 2nd barracks, Grynszpan

The letter left Herschel distraught and desperate, and his first instinct was to send all his savings to his family. He ended up arguing with his uncle over this plan, and he was persuaded not to do it, due to the low likelihood that the money would make it to his family. Just two days later, on the 6th of November, Herschel departed his uncle’s house announcing he would not return, slept in a hotel, and the next morning, at 9:30am on November 7th, 1938, managed to enter the German embassy in Paris by pretending to have to deliver an important message. Upon entering the office of diplomat Ernst vom Rath, he shot him. He had bought the gun that morning on his way to the embassy.

Two days later, on November 9, 1938, vom Rath died of his wounds. At his funeral he was declared a “blood witness” (Blutzeuge), i.e. a martyr who shed blood for the Nazi cause. In his funeral oration, Joachim von Ribbentrop declared “We understand the challenge, and we accept it.”

The same evening that vom Rath died, the 9th of November, 1938, Joseph Goebbels gave a speech inciting violence against Jews and instructing party officials not to to restrict anti-Jewish riots. Later that night, Reinhard Heydrich sent a teletype from Berlin to Gestapo and police office instructing police not to interfere with demonstrators acting against Jews, telling them to target only Jewish businesses and synagogues, ordering the seizure of Jewish property and instructing fire brigades to let synagogues burn.

That night and the following day More than 1,200 synagogues and prayer halls were burned and/or destroyed across Germany and two hundred or so more in Austria. Jewish cemeteries and schools were desecrated. Thousands of Jewish businesses were looted and sacked. Around 30,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps. 91 Jews were murdered. The next day Goebbels wrote in his diary “This is one dead man who is costing the Jews dear. Our darling Jews will think twice in the future before simply gunning down German diplomats.”

Below is an example of what remains now of one of the destroyed synagogues (the one in Eisenach, Germany, shown smoldering after Kristallnacht above). This site and others like it are marked on Google Maps these days as “ehemalige Synagoge” (one time synagogue).

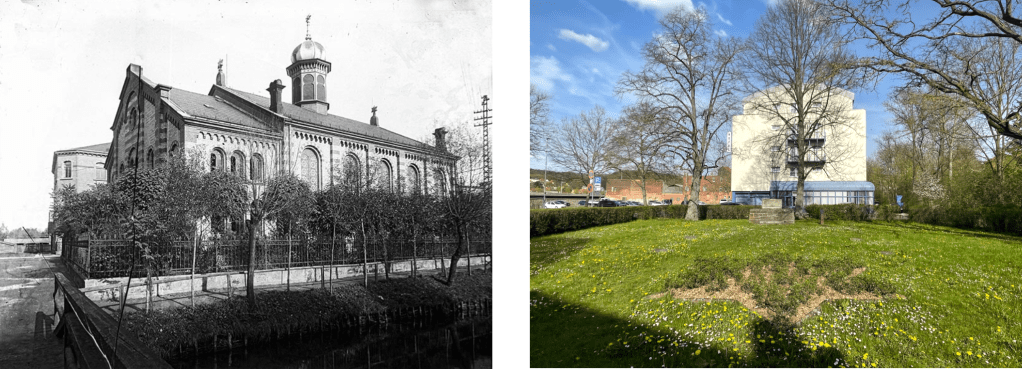

In Zbąszyń, the 1851 synagogue (see photos above) is now gone and in its stead there is an apartment building:

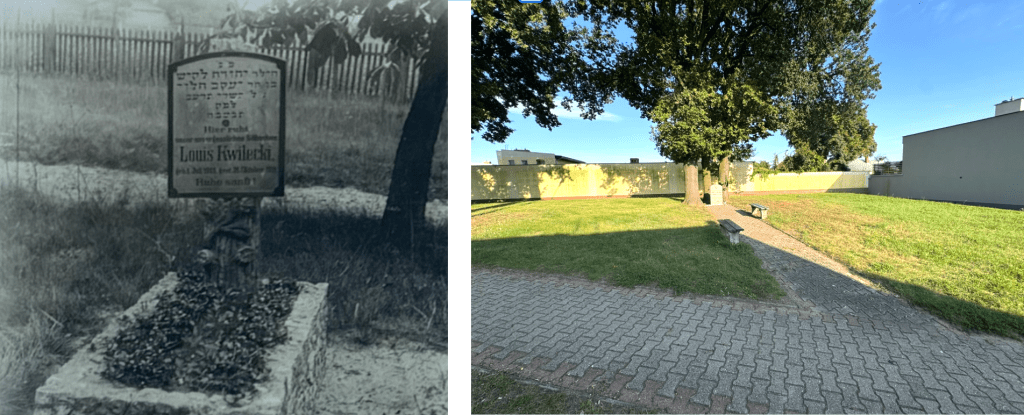

The Jewish cemetery in Zbąszyń is today a patch of grass. It was desecrated in 1939, although some of the grave remnants were still there at the end of World War II. Those remains were razed to the ground and liquidated completely in the 1970s. Now, a small memorial stone from 1992 commemorates what the lawn once was. It asks that one honor the site. I visited the place last week on September 13, 2025 and found it to be littered with broken glass bottles and beer cans. While cleaning up the trash I wondered about the futility of the act.

The Gryzbowski brothers were Jews who owned a flour mill in Zbąszyń that they used to house some of the Polenaktion Jews. Two Stolper stones mark the last place they lived in the town. The Polish inscription underneath Rafał Grzybowski’s name translates to “helped the deported during the Polenaktion, deported to the Kutno-Konstancja camp, murdered”.

In 1939, several months after their internment, some of the Jews in Zbąszyń started to be allowed to leave farther east into Poland. Like Rafał Grzybowski, the vast majority of them were almost certainly murdered. Kristallnacht was a prelude to the holocaust, which was a genocide in many acts with many actors. The Nazis found eager partners among the Poles, as evident already in the Białystock and Jedwabne pogroms of 1941 (this history is being erased today). 90% of the Jews in Poland were murdered in the holocaust, amounting to 3 million souls.

The Nazis relied on the high-precision geodetic surveys they had throughout the war. When US Army Major Floyd Hough entered Aachen, the first German city to fall to the Allies, on October 21st, 1944, he found a treasure trove of German maps bundled for evacuation, evidently left behind by German soldiers as they undertook a hasty retreat. The surveys were immediately useful to the Allies, helping artillery units on the front improve their targeting.

But it was the Red Army that liberated Zbąszyń during the Vistula-Oder offensive in January 1945. By the time they arrived there was no longer a Jewish community in Zbąszyń and there has not been one since. More than five centuries of a Jewish community erased by the German-Polish antisemitic vise that squeezed its Jews to death.

Recent Comments