In the last post I discussed the category of framed oriented tangles, which according to Shum’s theorem is a free ribbon category. As a corollary to Shum’s theorem, we may derive tangle invariants from any ribbon category. Let’s see how this works for the Kauffman bracket.

Consider planar diagrams, that is curves in the plane. These are like tangle diagrams only without self-intersections, i.e. no crossings. Just like tangles, they form a monoidal category since we can place them side by side or atop each other. Also just like tangles they have duality cups and caps.

Cup and Cap

Inspired by the definition of the Kauffman bracket, we extend the category of planar diagrams by linear combinations with coefficients polynomials in and mod out by the circle relation:

Circle Relation

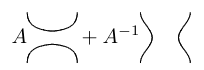

This gives a braiding and twist as in the calculations for the Kauffman bracket.

Braiding

Twist

The resulting ribbon category is called the Temperley-Lieb category, named for mathematicians who studied its implications in the context of statistical mechanics.

Now we have two examples of ribbon categories, the category of tangles and the Temperley-Lieb category. How else can we generate examples of ribbon categories? Recall that the category of finite dimensional vector spaces and linear maps formed a monoidal category with duals. We consider the subcategory of representations of an algebra .

An algebra is a vector space in which we have a multiplication and unit with the familiar properties of associativity and unitality. For example, given a vector space the space

of endomorphisms of

, that is linear maps

, forms an algebra where our multiplication is composition of linear maps and our unit is the identity map

.

is a representation of

iff there is a linear map

which preserves multiplication and unit.

A Hopf algebra, in addition to having a multiplication and unit, also has maps called comultiplication, counit which are coassociative, and counital where

is the field of scalars. This guarantees that the category

of finite dimensional representations of

is monoidal since we can define representations

and

. We also require a map

called the antipode which switches the order of multiplication and is the convolution inverse to the identity. This guarantees that

has left duals with

.

If there are elements such that

is a braiding, where

is the swap map

and where

is a twist, then we call

a ribbon Hopf algebra. Clearly then

is a ribbon category.

Surprisingly, ribbon Hopf algebras turn up in the study of Lie algebras. One may “quantize” a Lie algebra, deforming it by a formal parameter meant to mimic Plank’s constant and the result is a ribbon Hopf algebra. This discovery led to a whole slew of new invariants and a new understanding of old invariants. For instance the Jones’ polynomial and the Kauffman bracket are related to the quantization of the most basic Lie algebra

. Invariants of tangles derived from quantized Lie algebras are called Reshetikhin-Turaev invariants or simply quantum invariants. When applied to links they give polynomials in a variable

.