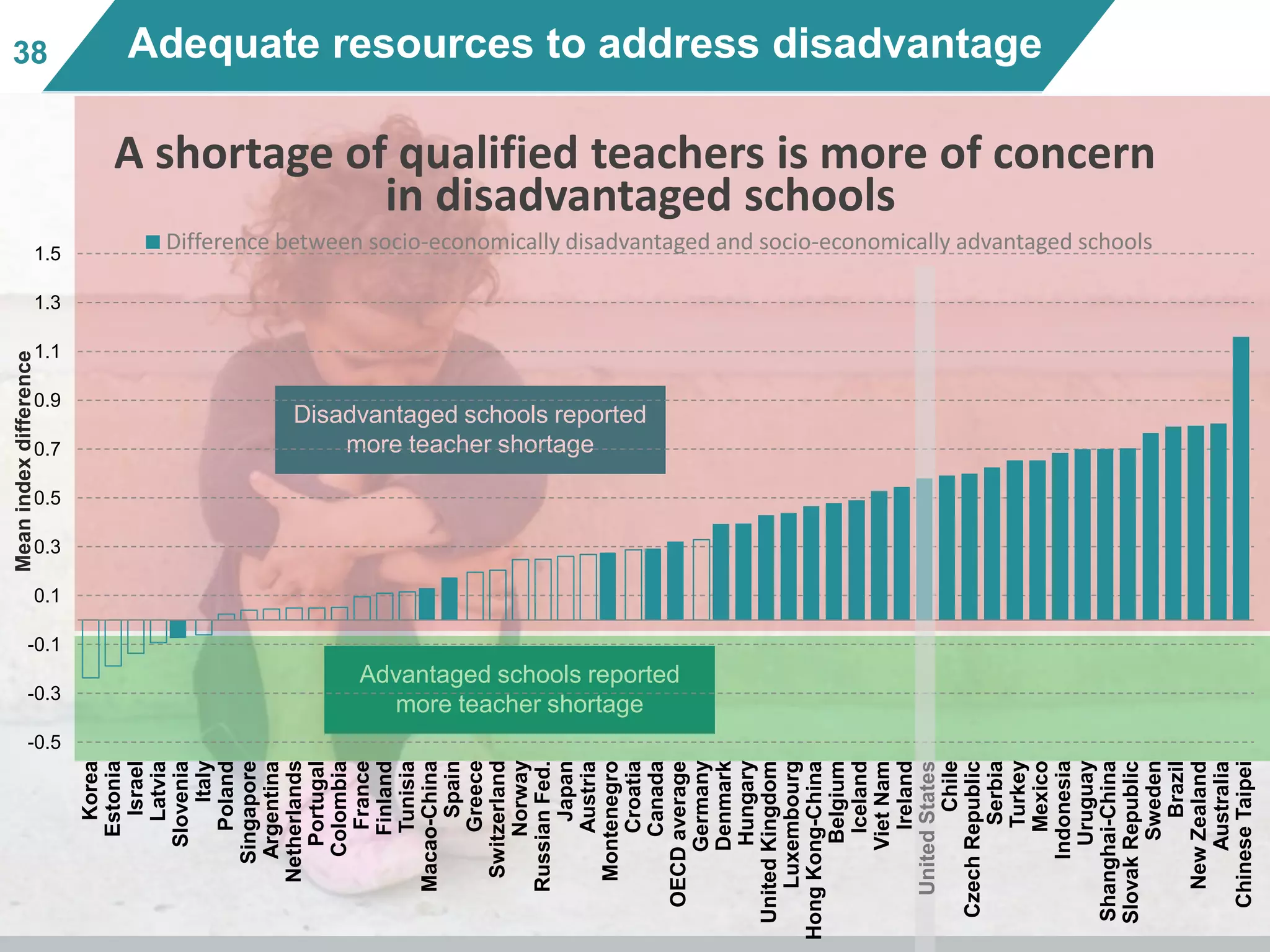

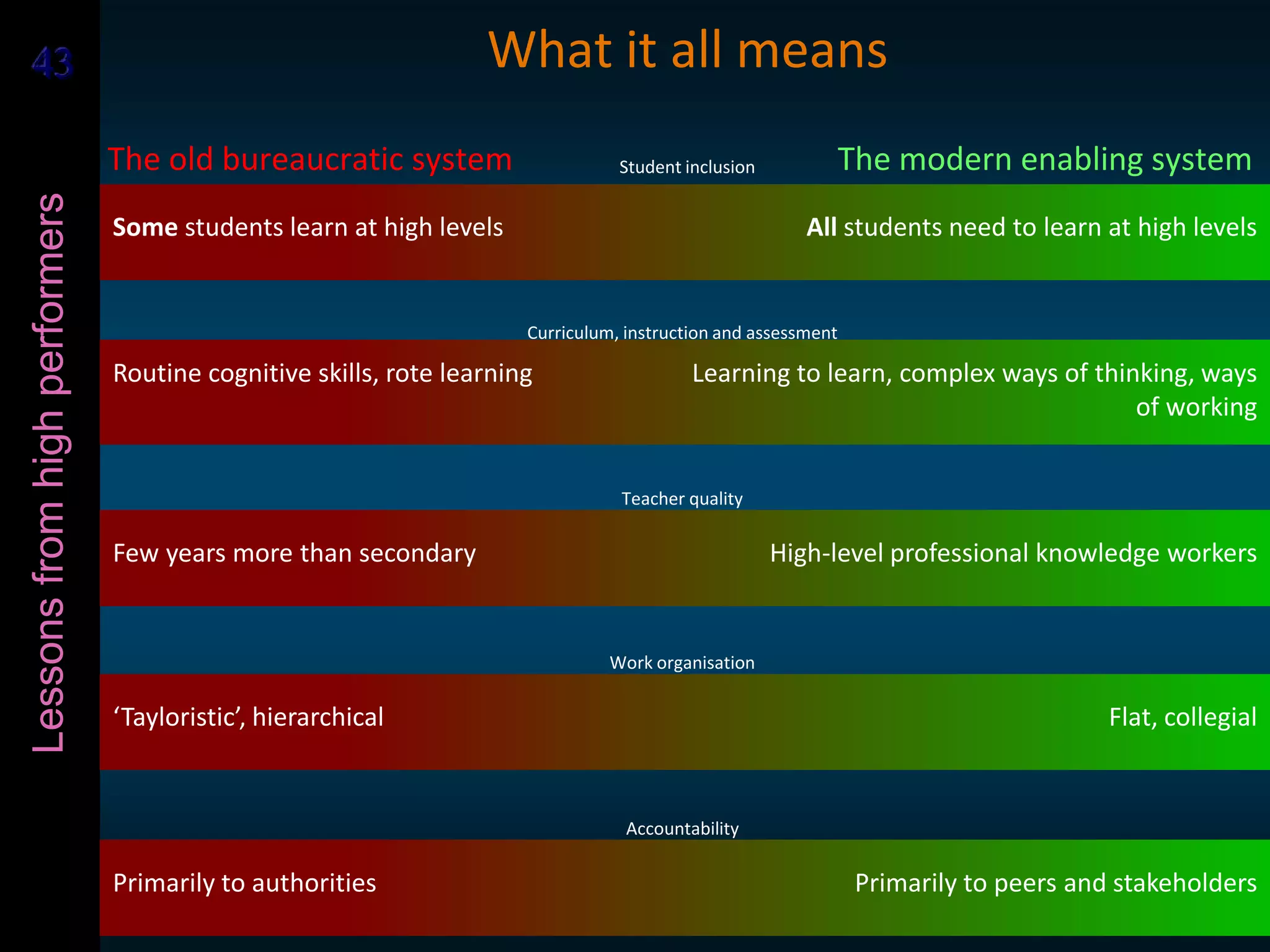

This document discusses education systems and student performance based on PISA test results from 65 countries. It finds that students who score higher on literacy skills tests as 15-year-olds are more likely to have positive adult outcomes. Countries with more equitable education systems and less socioeconomic impact on performance tend to have higher average scores. High-performing education systems emphasize universal standards, accountability, and coherence across the system.