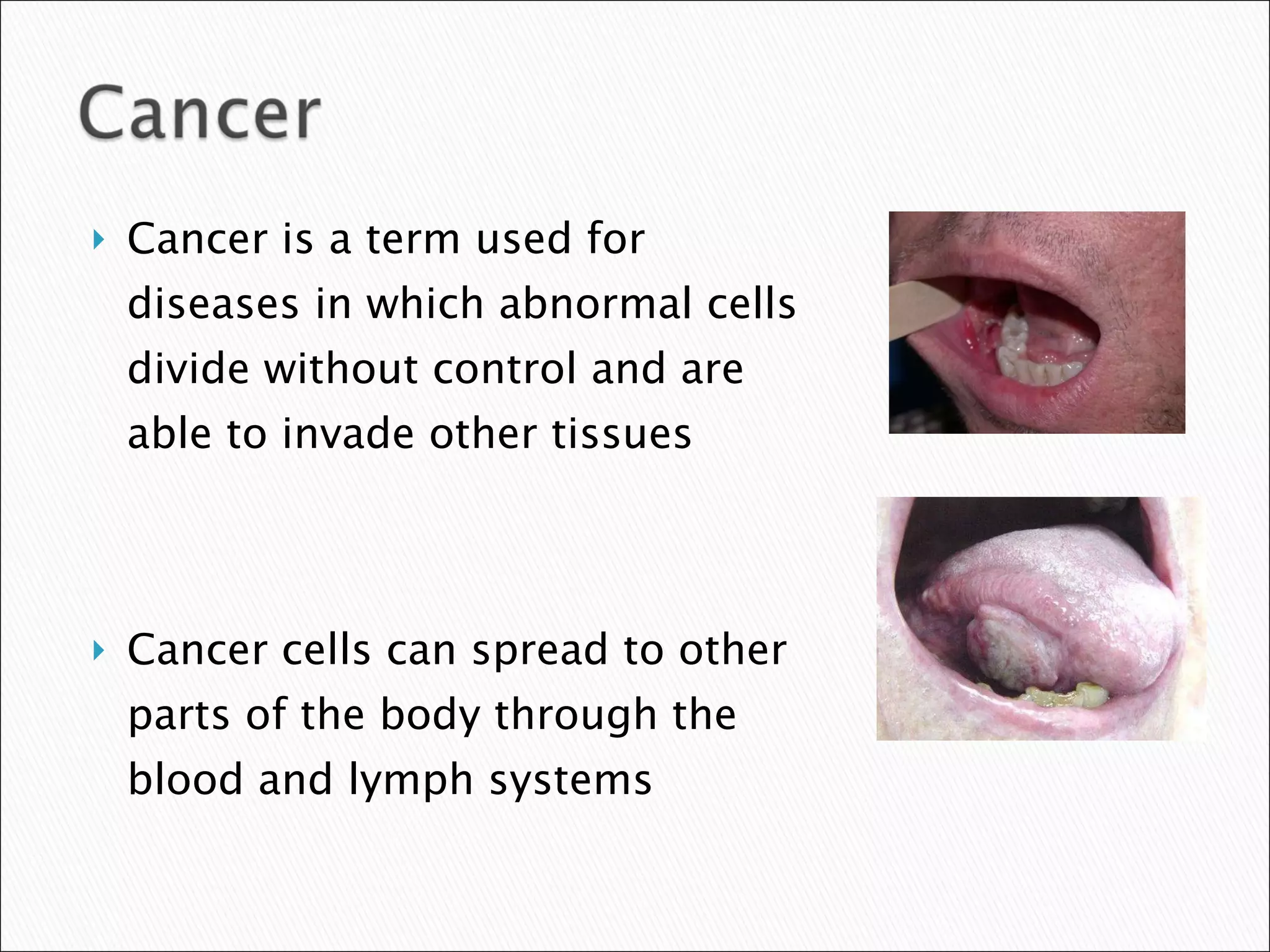

Oral cancer is a term used for cancers occurring in the oral cavity. It is the most common type of head and neck cancer. Risk factors for oral cancer include tobacco use, heavy alcohol consumption, human papillomavirus infection, and sun exposure. Data from the SEER program shows that from 2002-2006 the age-adjusted incidence of oral cancer in the United States was 10.4 per 100,000 people, while the age-adjusted mortality rate was 2.6 per 100,000. Survival rates are lower for advanced stage cancers, cancers in black males, and HPV-negative tonsillar cancers.