After completing this lesson, you will be able to:

Encourage active participation by the patient in decision-making and explain choices or rights to the patient in a patient-centered manner

Assess patient desire and capacity to be involved and responsible in the decision-making process

Determine patient preferences and priorities for treatment

Identify strategies to assist patients in discussing preferences and priorities with clinician

Support the patient in the decision-making process in alignment with desired level of engagement

Describe a treatment plan

Assess barriers to patient adherence to the plan

Develop a plan with the patient for addressing adherence challenges

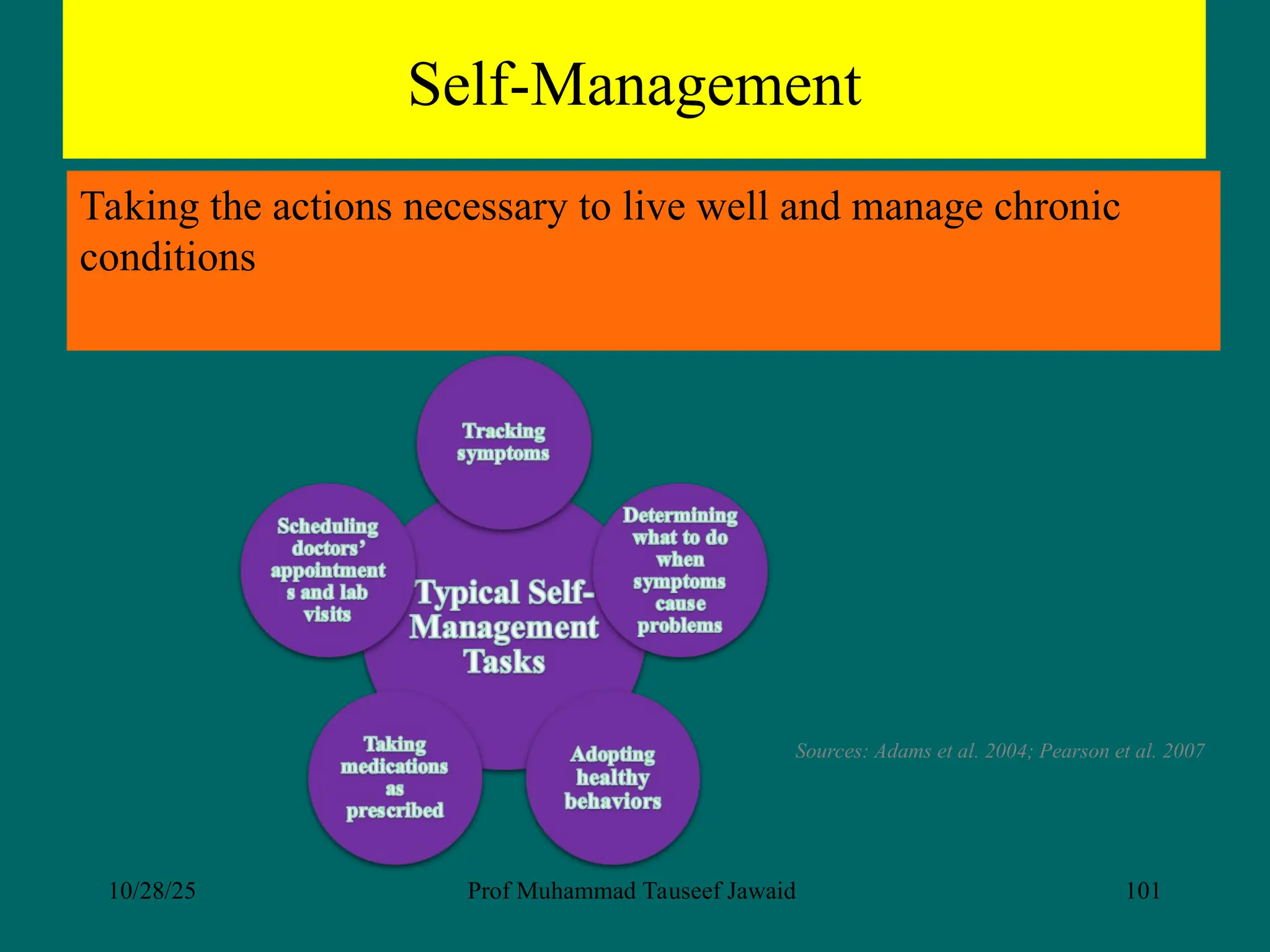

Identify self-management and health promotion resources

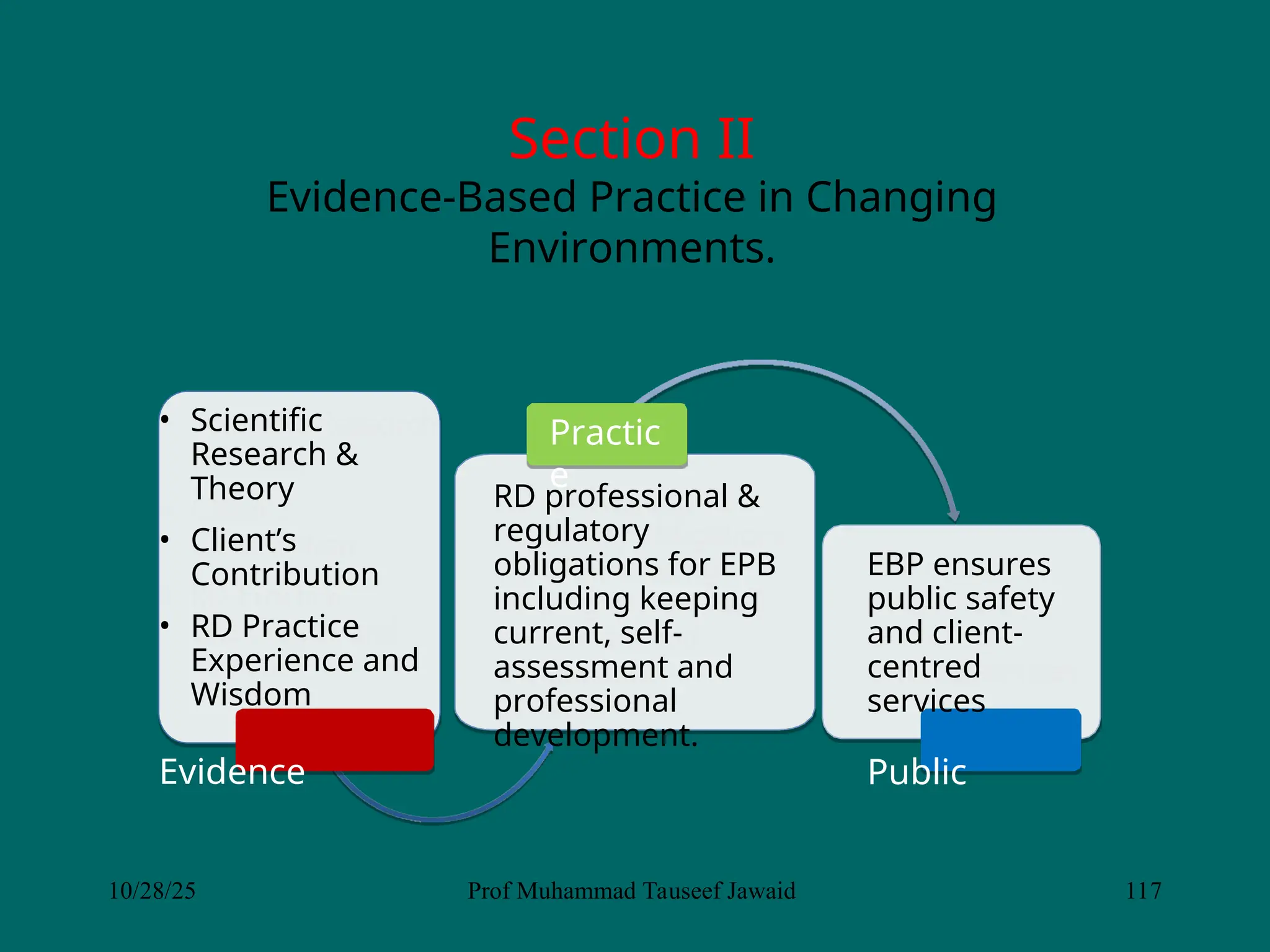

![“Evidence-based decision-making

refers to making decisions that affect

[client] patient care based on the best

available evidence”

10/28/25 Prof Muhammad Tauseef Jawaid 114](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lectureconceptofhealthshareddecisionmaking2025-251028042501-7052fb6f/75/Lecture-Concept-of-Health-Health-Literacy-and-Shared-decision-making-2025-ppt-114-2048.jpg)