James Watson, who described himself as “not a racist in a conventional way”, has died at the age of 97. Below is a review of an obituary for Dr. James Watson published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on November 7, 2025. The obituary is in black and the review comments are in red.

Jim Watson made many contributions to science, education, public service, and especially Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL).

In the realm of science, several of the contributions James Watson took credit for were not his (see below). In terms of education, his focus was on bringing a single Eton boy every year to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory for a research experience during the boy’s gap year after high school (the boys would frequently stay at his house). Eton, an all-boy boarding school, is Britain’s most elite school (CSHL oral history, 1997). Insofar as public service, Watson’s public record was not one of civic engagement or humanitarian contribution. His tenure as the first head of the Human Genome Project ended quickly in conflict (see below) and his public statements regarding genetics and race, gender, and intelligence was widely condemned (source: Amy Harmon, 2019)

As a scientist, his and Francis Crick’s determination of the structure of DNA, based on data from Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins and their colleagues at King’s College London, was a pivotal moment in the life sciences.

Franklin did not just provide data that enabled Crick and Watson to determine the structure of DNA. Yes, with her student Raymond Gosling she generated high-quality X-ray images of DNA, most famously Photo 51, which provided clear evidence that DNA forms a helical structure. But Franklin did much more and was an equal scientific contributor to the elucidation of DNA’s structure, whose experimental rigor and insights were central to solving the double helix. Franklin’s X-ray diffraction work distinguished the A and B forms of DNA, resolving confusion. Her measurements revealed that DNA’s unit cell was huge and had a C2 symmetry, implying two antiparallel sugar-phosphate strands. She confirmed the 34 Å helical repeat in the B form and identified the phosphate backbone’s exterior location. Though she did not derive complementary base pairing, her late-stage notes show that she recognized DNA could encode biological specificity through any sequence of bases, anticipating the idea of informational coding (Cobb and Comfort, Nature, 2023).

Watson, along with Crick and Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Watson also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Gerald Ford and the National Medal of Science from President Bill Clinton, among many other awards and prizes.

It is true that Watson received these awards. Coincidentally, William Shockley was also awarded the Nobel Prize around the same time as Watson (physics, 1956) and he promoted racist eugenics, arguing that people of African Ancestry posed a “dysgenic risk”, as well as advocating for sterilization. He used his Nobel prestige to advance his malicious and scientifically bankrupt ideas (source: Scott Rosenberg, 2017)

While at Cambridge, Watson also carried out pioneering research on the structure of small viruses. At Harvard, Watson’s laboratory demonstrated the existence of mRNA, in parallel with a group at Cambridge, UK, led by Sydney Brenner.

One of his colleagues at Harvard, E. O. Wilson, once called James Watson “the most unpleasant human being I have ever met” (source: Amanda Gefter, 2009).

His laboratory also discovered important bacterial proteins that control gene expression and contributed to understanding how mRNA is translated into proteins.

The discovery of important proteins that control gene expression in bacteria, notably the lac repressor, was made by Francois Jacob and Jaques Monod.

As an author, Watson wrote two books at Harvard that were and remain best sellers. The textbook Molecular Biology of the Gene, published in 1965 (7th edition, 2020), changed the nature of science textbooks, and its style was widely emulated.

In this textbook Watson got the central dogma wrong, presenting it in a profoundly misleading way. (source: Matthew Cobb, 2024).

The Double Helix (1968) was a sensation at the time of publication. Watson’s account of the events that resulted in the elucidation of the structure of DNA remains controversial, but still widely read.

Prior to the publication of The Double Helix, Francis Crick wrote that “If you publish your book now, in the teeth of my opposition, history will condemn you”. Watson published the book anyway (source: letter by Francis Crick, 1967) .

As a public servant, Watson successfully guided the first years of the Human Genome Project, persuading scientists to take part and politicians to provide funding.

Watson resigned from the Human Genome Project due to conflicts of interest related to holdings of his in biotechnology companies and due to his insistence that cDNA should not be sequenced leading to conflicts with NIH director Bernadine Healy, with whom he also clashed on patenting of expressed sequence tags (source: Christopher Anderson, 1992). Fortunately, thanks to the vision of Bernadine Healy, who was the first female director of the NIH, cDNA technology was pursued and led to RNA-seq which, along with DNA-seq, is today the most widely used genomics assay.

He created the Ethical, Legal and Social Issues (ELSI) program because of his concerns about misuse of the fruits of the project.

Watson reportedly configured ELSI so as to undermine its ability to interfere with the human genome project: “I wanted a group that would talk and talk and never get anything done and if they did do something, I wanted them to get it wrong. I wanted as its head Shirley Temple Black” (source: Lori Andrews, 1999, Dolan et al., 2022).

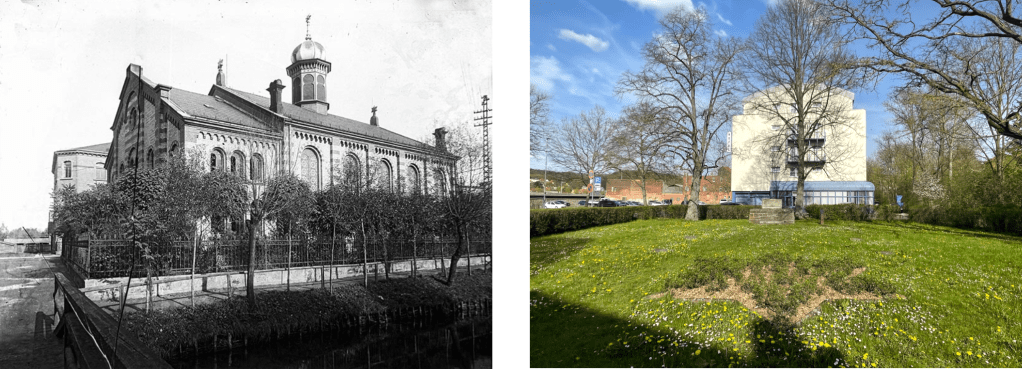

Watson’s association with Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory began in 1947 when he came as a graduate student with his supervisor, Salvador Luria. Luria, with Max Delbruck, was teaching the legendary Phage Course. Watson returned repeatedly to CSHL, most notably in 1953 when he gave the first public presentation of the DNA double helix at that year’s annual Symposium. He became a CSHL trustee in 1965.

James Watson did not credit Rosalind Franklin in his presentation of the DNA double helix; he did not even mention Rosalind Franklin in his Nobel, although he did admit that people found him unbearable (source: Nobel Banquet speech, 1962).

CSHL was created in 1964 by the merger of two institutes that existed in Cold Spring Harbor since 1890 and 1904, respectively. In 1968, Watson became the second director when he was 40 years old. John Cairns, the first director, had begun to revive the institute but it was still not far short of being destitute when Watson took charge. He immediately showed his great skills in choosing important topics for research, selecting scientists and raising funds.

On the matter of selecting scientists, Watson once remarked “Whenever you interview fat people, you feel bad, because you know you’re not going to hire them” (source: Tom Abate, 2000). On the matter of raising funds, it seems that James Watson’s network included Jeffrey Epstein, with whom he reportedly met within two years before Epstein’s arrest in 2019 (source: Business Insider).

Also in 1968, Watson married Elizabeth (Liz) Lewis, and they have lived on the CSHL campus their entire lives together. Jim and Liz have two sons, Rufus and Duncan. As with the former Directors, they fostered close relationships with the local Cold Spring Harbor community.

In 1969, Watson focused research at CSHL on cancer, specifically on DNA viruses that cause cancer. The study of these viruses resulted in many fundamental discoveries of important biological processes, including the Nobel prize-winning discovery of RNA splicing. Watson was the first Director of CSHL’s National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Center, which remains today.

On the matter of cancer, James Watson delivered a lecture at UC Berkeley in 2000 where he talked about an experiment to protect against skin cancer. He claimed that in an experiment by scientists at the University of Arizona, who injected male patients with an extract of melanin to test whether they could chemically darken the men’s skin as a skin cancer protection, they observed an unusual side effect, namely that the men developed sustained and unprovoked erections (source: Tom Abate, 2000).

Watson was passionate about science education and promoting research through meetings and courses. Meetings began at CSHL in 1933 with the Symposium series, and the modern advanced courses started with the Phage course in 1945. Watson greatly expanded both programs, making CSHL the leading venue for learning the latest research in the life sciences. Publishing also increased, notably of laboratory manuals, epitomized by Molecular Cloning, and several journals began, led by Genes & Development and later Genome Research. He encouraged the creation of the DNA Learning Center, unique in providing hands-on genetic education for high-school students. There are now DNA Learning Centers throughout the world.

The DNA learning center page on Rosalind Franklin states “The X-ray crystallographic expert, hired for her skills, and known to be methodical. Don’t call her Rosy!” (source: DNA learning center)`

Through a substantial gift to CSHL in 1973 by Charles Robertson, Watson started the Banbury Center on the Robertsons’ 54-acre estate in nearby Lloyd Harbor. Today, this center functions as an important “think tank” for advancing research and policies on many issues related to life and medical sciences.

The Banbury Center was founded as an old boys club. Meetings are invitation only, with invites by the old boys for other old boys. I attended a meeting in 2004 on functional genomics which consisted of 33 invitees of which 33 were men, despite the fact that many of the leading genomics scientists at the time were women. At the meeting I had dinner with James Watson, during which he took the opportunity to denigrate Rosalind Franklin and the Irish (source: Banbury Center, 2004).

Watson remained in leadership roles at CSHL until 2000, and then continued as a member of the faculty. However, his remarks on race and IQ in 2008 led the CSHL Board of Trustees to remove him from all administrative roles and his appointment as a CSHL Trustee. When he made similar statements in 2020, the board revoked his Emeritus status and severed all connections with him.

Watson made racist and sexist remarks not only in 2008 and 2020 but throughout his life (source: James Watson in his own words).

Watson’s extraordinary contributions to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory during his long tenure transformed a small, but important laboratory on the North Shore of Long Island into one of the world’s leading research institutes.

Watson was the director of CSHL from 1968 – 1994 but there have been many other individuals who were key in establishing CSHL as a leading research institute: Barbara McClintock (discovered transposons) was at Cold Spring Harbor from 1941 until her death in 1992 (source: Wikipedia). She was recruited by Milislav Demerec (director 1941 – 1960). Bruce Stillman (director since 1994) has been instrumental in establishing the CSHL graduate program, the Genome Research Center, and under his watch it became a top-10 biomedical research center (source: Wikipedia).

Recent Comments